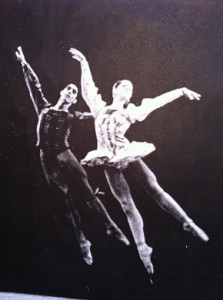

Marina at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet

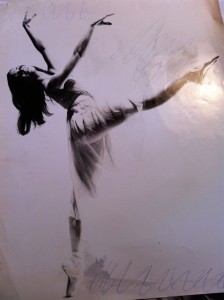

Photo courtesy of Marina Eglevsky

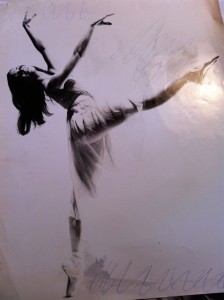

Photo credit: Peter Garrick

This month, we continue with Part 2 of my interview with Marina Eglevsky. We take up the thread of this portion of the interview by continuing with her years at the Hamburg Ballet, after having left Harkness Ballet:

Q: From leaving Harkness and joining Hamburg Ballet, how long did you stay there?

A: We stayed there for a couple of years, but we didn’t like living in Germany too much, so we went back to Winnipeg (we had an open contract there — as we were only on a leave from the company). A lot of things happened there – I had a major accident, someone dropped me in a lift, and I didn’t think I could recover – political issues as well – I felt like I was an artist and was in a protective bubble against political issues and the company was disbanded and for the second time we were in a company that was disbanded — and when that bubble was burst and with my injury — I didn’t want to dance anymore. My husband wanted to direct and so he found a director position at North Carolina Dance Theatre, so I went with him and that’s where I started to teach, that’s when my teaching career started.

Q: After you recovered from the injury – did you go back to dancing or guesting?

A: I did, I was asked to join the National Ballet of Canada and also to ABT (American Ballet Theatre) or John Neumeier (Hamburg) and so I had a choice — to leave my husband, get in shape and go out to those companies and I just felt like — I just didn’t get it back, after what had happened at Winnipeg, so I went back to my husband in North Carolina. Then Agnes DeMille asked me to dance in Brigadoon on Broadway – I did that – but, my steam for being in a major company again just kind of ran out, so I went back to North Carolina and started teaching and started a bakery business and then I decided I wanted to go into medicine.

Q: Was that the transition into bodywork? Is that how it all started?

A: Yes.

Q: So, was it at this point, that you intermittently guested with other ballet companies or were you pretty much teaching at that point?

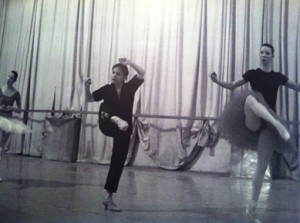

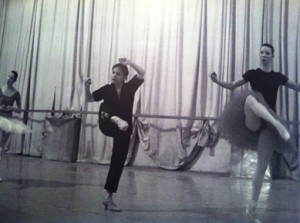

Marina staging at the Bolshoi

Photo courtesy of Marina Eglevsky

Photo credit: Damir Yusupov

A: I was teaching and staging — because my father had died in 1977, and before he died, he coached me in these Balanchine ballets to be able to stage them. After he died in 1977, I staged them — these ballets that he had in the Eglevsky Ballet repertoire, that Balanchine had given him. I continued to do a lot of teaching and staging in North Carolina – continued with my bakery business for awhile, and when I decided to go into medicine, I decided to stop all ballet, but it never happened, I kept being asked to stage.

Q: So when you had a desire to go into medicine, what form did that take in the beginning? Did you want to go to medical school and start there, or did you want to go into bodywork – how did that all start?

A: I wanted to go to medical school and I wanted to be a doctor, I spent some time with friends in Wyoming to get away – I was staying there for the summer and I enrolled into school in Laramie at the University there – they were trying to get adults back into school, so it was so cheap and they had a fast track program. To be a doctor — like in 7 years — and you’re done. At the time, I thought it was ideal, and I tried it. I started it and got honorary grades, and then went to Miami City Ballet, to stage a couple of ballets, and got back for 2nd semester of med school and I was so behind, and I didn’t do so well. And, my grandmother got sick and my mother needed help with her school – so, I had to get back to New York, so that was the end of that. But, I didn’t want to stop so I consulted with a psychic who said: “the best thing for you is alternative medicine, and there is a wonderful school in New Mexico”, so I ended up doing that and I fell in love with that, because it was more me.

Ever since I was little and I was dancing, I was basically studying alternative medicine to take care of myself — it was a fascination of mine — not really medicine per say, but the preventative approach.

Q: How to help dancers recover and prevent injuries?

A: Yes — which dancers need to know more about — you do everything you can do to get in a company with the body you have, you don’t want to lose that, and you’re always exhausted, so taking care of yourself doesn’t often enter a dancer’s mind. {Interviewer: I know for myself, everything goes out of my brain, strive to try my best in class and dance, without thinking of my body or injury.}

Q: From the school in New Mexico, how did that transpire into bodywork, you’d said you’re also a massage therapist as well?

A: My interest was more in medical massage, not just flat out massage, I had no interest in that, but to focus on specific problems, that was more like medical school, studying problems, that was my passion. In our first class, the very beginning of school, we had Rosen Method bodywork, I mean once I left a ballet company, I was lost – I didn’t find the same way of identifying myself in anything I did, I couldn’t find that and I really suffered from that.

I remember the first class, I’m sitting at the table with my hands on somebody, had no idea what it was — you just sit there next there next to a person, you put your hands on that person and they guide you thru a very intuitive process, watching yourself, watching this other person. The first day, I suddenly had this feeling that I’d found myself, that I’d found myself as a dancer – it was so amazing, I couldn’t believe it – it was like this self-centering which then goes out and meets another person. That’s what you do on stage, you’re so self-centered, then you’re meeting, going in, and it turns around and goes out and connects with the audience – and the audience, I never got confused whether there’s 100 or 1000 or 3,000 people – it always felt like one body, one person that I was speaking to – that’s what it felt like in this work – it was so profound for me, I never lost that, that wonder with that.

Q: It sounds like a real passion of yours, a true passion of yours, I mean, hand in hand with dance?

A: Yes, that’s the big thing now is to be in touch with one’s self and able to function in the outer world and at the same time – you’re in touch with both worlds at the same time.

Q: So, you studied Rosen Method bodywork in New Mexico and I’m assuming there were more methods that you studied there?

A: Yes, after New Mexico, I continued to study at the school that was formed to study Rosen, so I studied there and I actually wanted to train with Marian Rosen, who was in Berkeley. My whole upbringing had taught me to study with the greats – and the greats was with Marian, so I came to Berkeley in 1994 to study with her.

Q: Is that what brought you to the San Francisco Bay Area?

A: Partly, I did one more try at med school, and there was only one in New Mexico, Marian was here and so were other medical programs, so I looked into them – I was accepted into Cal, and I looked into a couple of other programs – but, I never got away from ballet, and Rosen Method, and preventative medicine – it just really hits me.

Q: So, through out all this you were still being called to set Balanchine ballets on ballet companies?

A: Yes.

Q: And, also perhaps to do some guesting in ballets or at this point, were you no longer doing that?

A: No, I stopped – I did my last performance in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I actually choreographed something on myself.

Q: Was it with the Santa Fe Ballet?

A: It was then — it was what is now the Aspen Ballet — the Aspen Ballet School took over the school in New Mexico where I was teaching when I was there.

End of Part 2 – stay tuned for next month’s 3rd and final installment.

As the old year passes, I thought a look back at some of this year’s highlights with some of the major ballet companies (and not so major) would be a fitting way to look at where we’ve been and look forward to where we’re going. Below are 10 of my picks for a brief look at the world in ballet for 2016.

As the old year passes, I thought a look back at some of this year’s highlights with some of the major ballet companies (and not so major) would be a fitting way to look at where we’ve been and look forward to where we’re going. Below are 10 of my picks for a brief look at the world in ballet for 2016.